Desert

The desert (from the Latin deserere, to abandon) is a habitat with poor rainfalls. In many deserts, the annual rainfall is below 50 mm, but it can even be zero. In this ecosystem, the shortage of water is the main ecological factor affecting vegetal and animal life. As well as the shortage of rains, it is also its variability over the year that strongly affects life: for comparison, just think that rainfalls in Europe vary by 20% over the year, while in Sahara this variability reaches 80-150%. This involves occasional violent downpours during which it can rain more than over several consecutive years. Deserts may be either cold or hot. Cold deserts are at high altitudes, where winter temperatures can be below zero, such as the Gobi Desert, protected by the air masses bringing rain from high mountain ridges. In hot deserts, the atmospheric temperature during the day can reach 50°C, while the surface temperature of the sand can rise to 90°C. At night, the ground and the air quickly cool down, with temperature differences of over 20°C. In such a inhospitable environment, all the living beings must adapt themselves: to make up for the shortage of water, the most varied forms of adaptation have developed, even if biodiversity is still low, since between 20 to 400 plant species can be found in 150,000 square kilometres (one half of Italy).

World deserts

Deserts extend from the 20th northern parallel to the 20th southern parallel. 15% of all lands above sea level are considered medium dry, another 15% dry and 4% extremely dry. Extremely dry deserts have no rainfalls at all for periods of over one year. This is typical of real deserts, such as the Sahara, part of the Arabic desert; the Mojave Desert in North America; the Namibian desert and part of the Kalahari; the Atacama Desert in Latin America; the Gobi Desert in Asia and part of the Australian desert.

Oases

An oasis generally forms where a water table is closer to the earth's surface so that the water that can let life develop comes to the surface. Occasionally, oases are artificially made by digging wells, even to a depth of a few kilometres, to reach the water table from which water can be taken later with a pump or bucket. The vegetation of these habitats generally consists of date palms and small vegetable, fruit and cereal plantations. They need water, which is channelled and brought to the vegetable gardens of the oasis.

Plants of the desert

The vegetal life of the desert comprises annual, ephemeral and perennial species. Annual plants are all those plants, mostly herbaceous, having a life cycle of less than a year, such as, for instance, the Panicum turgidumwhich is an evergreen plant in moister alluvialsoils, while in dry areas it becomes a deciduous plant, i.e. a plant that loses its leaves. Ephemeral plants are those plants that are born only after occasional rains and reproduce and die before a new drought comes, and they typically have therefore an extremely short life cycle, for instance the Alyssum alyssoides…

Animals of the desert

Impressive cases of adaptation to this inhospitable habitat, where heat and drought are the main limitations to the development of life and also to the availability of food, can also be found in the animal kingdom. During the summer or particularly long drought periods, some desert animals "aestivate", i.e. they reduce their activity by hiding under the rocks or underground, just as, in milder climates, many living beings hibernate in winter. Aestivating animals include, for instance, some species of reptiles and the desert snails which come to life only after rains: when moisture decreases, they hole up in their shells waiting for new rains in a dormant state that can last up to five years.

Desert formation

A desert forms when there has been a shortage of rain for a long time. It may have different geological conformations - mainly due to the effect of the wind (wind erosion). There are sand deserts, called erg, rock deserts, called hammada, and pebble deserts, the serir.

The history of a desert can be studied through palaeontology. During the Pleistocene (1 million years ago), where there are deserts now, rainy periods followed each other during the glaciations, while dry periods followed each other in warmer times.

The long history of the Sahara

The origins of the Sahara Desert, the largest hot desert and the largest desert in the world, date back to approximately 600 million years ago. The sea submerged the region over and over again, depositing its sediments; whenever it resurfaced, it was alternately covered by forests, savannahs and even marshlands. During that time, trees, such as oaks, cypresses, olive trees and Aleppo pines, grew in the area.

The dinosaurs of the Gobi

The Gobi Desert, at the south-western tip of Mongolia, is now one of the most inhospitable areas in the world, but between 130 and 65 million years ago it was a region brimming with life, with large lakes and rivers. It's here that, since the early twentieth century, the palaeontologists have been finding extremely rich deposits of fossils from the Cretaceous Period, when dinosaurs got to the height of their development before disappearing.

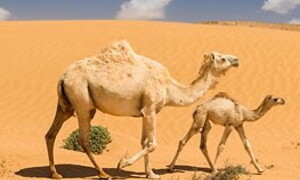

Despite the desert being so inhospitable, there are ethnic groups living in these places; they are groups of people that have to keep moving in caravans in search of places with water and food, defying the greatest risks: sandstorms, silted up wells and loss of bearings due to the lack of points of references. Some of these peoples are the Berbers of North Africa, that include the Kabilis and the Tuaregs, the Bedouins of the Arabic deserts, the Bejas in Namibia, the Sans in the Kalahari Desert and the Australian Aborigines.

The Tuaregs. The epitome of life in the desert are the Tuaregs, who for centuries have spent their lives riding their dromedaries along the Saharan tracks. Also called the "blue men" for the typical veils they wear to protect themselves from the sand and the heat, these people live in camps of tents built of dozens of goatskins painted in red ochre ad skilfully sown together by their women to guard all the items and tools of everyday life. The Tuaregs mainly live on products derived from their animals. Their foods are curdled milk, fermented butter, dates and cereals (millet in particular) from which they make flour. They rarely eat meat, but when they have guests they just have to honour them so they kill a goat according to Muslim traditions. Water is carried in scooped-out and sun-dried pumpkins, whose decorated surfaces hint at the groups who produced them. Originally, the Tuaregs were a nomadic people, but later on many conflicts and French colonisation pushed many of them to lead a sedentary life and the few nomadic ones that have been left live on the products of their animals and other foodstuffs they obtain through trade and breed horses and dromedaries. They produce handicrafts, for instance engraved silverware, they tan hides, make mats and produce rugs and textiles out of dromedary wool. Farming as well as high-level handicrafts are produced by lower castes, who live sedentarily in the oases. Today, some Tuaregs have found employment in the service sector, especially tourism: since they know the desert so well, they work as tour guides.

The Bejas. If the Tuaregs can be regarded as the "undisputed masters of the Sahara", the Bejas have always inhabited the large expanses of the Nubian desert. Most Bejas (approximately 1.5 million overall) live in the north-east of Sudan. They are called "Fuzzy-Wuzzies” because of their frizzy hair. For over 4,000 years, the Bejas have been running through this hot country and the bleak hills of the Red Sea in search of pastures for their camels, cattle, sheep and goats. They were feared for the quick raids they made into the rich towns along the Nile. After sacking the town, they hid in the desert of which they knew every nook and cranny and the wells where they could find water, even the most secluded ones. They are valiant and strong people, so much so that they did not only resist the pressures of the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, but in the 19th century they even won a battle against the British army, which were much better equipped and trained. Their only weapons have always been: silver-inlaid swords, bent knives, elephant-skin round shields and a very old weapon, the "throw stick", which had already been used by the Egyptians for hunting at the time of the Pharaohs.

Farming in the oases

In desert areas farming develops in oases. In the beginning there may be one palm only, planted in a dug-out area and surrounded by dead branches to protect it from the sand. Large crops develop over time, but the water needed for the vegetation to grow does not flow out freely. A tiring and rigorous work must be carried out by man to take water from underground. With time, man has built underwater tanks to collect water and long channels to carry it. They need constant maintenance to remove the sand or stones that could settle there and obstruct them.

The gold of the desert

The economic importance of the desert is also related to the exploitation of its mining resources, an activity which dates back to the antiquity. In Egypt, for instance, during the Roman rule, red porphyry was quarried to decorate great public buildings and the emperor's houses. The importance of red porphyry was probably not only related to its beauty, but also to the fact that the colour purple was chosen as the royal or imperial colour: its name, “porphyrites", actually comes from “porphyra”, purple.

Diamonds in the desert

Another human settlement in this hostile ecosystem has to do with its mineral resources: from gold to diamonds, from oil to many minerals. As early as the Ptolemaic era in ancient Egypt, the slaves toiled all through their lives to extract gold from quartz using primitive stone tools. Even now, a large part of the Namibian and South-African desert is exploited for its diamonds. Evidence of this activity is the old mining village of Kolmanskop, now a real ghost town neighbouring on this forbidden town. It was founded around 1920 after finding diamonds in the area, it quickly expanded into a local work and residential centre and was completely deserted by 1956.

The desert for the tourists

Another economic resource of the desert concerns tourism: it's hard to resist its charms. Many people are attracted by the silence and width of these picturesque, unique places. This is why camps have been fitted out to accommodate tourists from all over the world all through the year and as a basis for guided tours. Another tourist attraction that has to do with the desert is the “Paris-Dakar” car and bike race along a 10,000 km track from France to Senegal, through Spain, Morocco, Mauritania, Mali.

Desertification

According to the figures reported by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 25% of the earth’s land is threatened by desertification. The lives of over one billion people in over 100 countries are at risk since farming and cattle breeding become less productive. Desertification does not mean the deserts are still expanding or taking over the neighbouring lands. As defined by the UN Conference on “Environment and Development” held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, desertification is a process of “deterioration of the arable land into dry, medium dry and sub-humid dry areas as a consequence of many factors, including climatic changes and human activities”.