Let’s find out about viruses

29 february 2020

Parasites at the edge of life

Virus is a Latin word meaning poison. Viruses are pathogens (they make you ill) but they do not feed, breathe, move or reproduce independently. So then, what kind of life is it? None, viruses are not technically alive. In order to exist they must necessarily enter other organisms, which is why viruses are unrivalled parasites. There are no living beings immune to virus attack, not even bacteria.

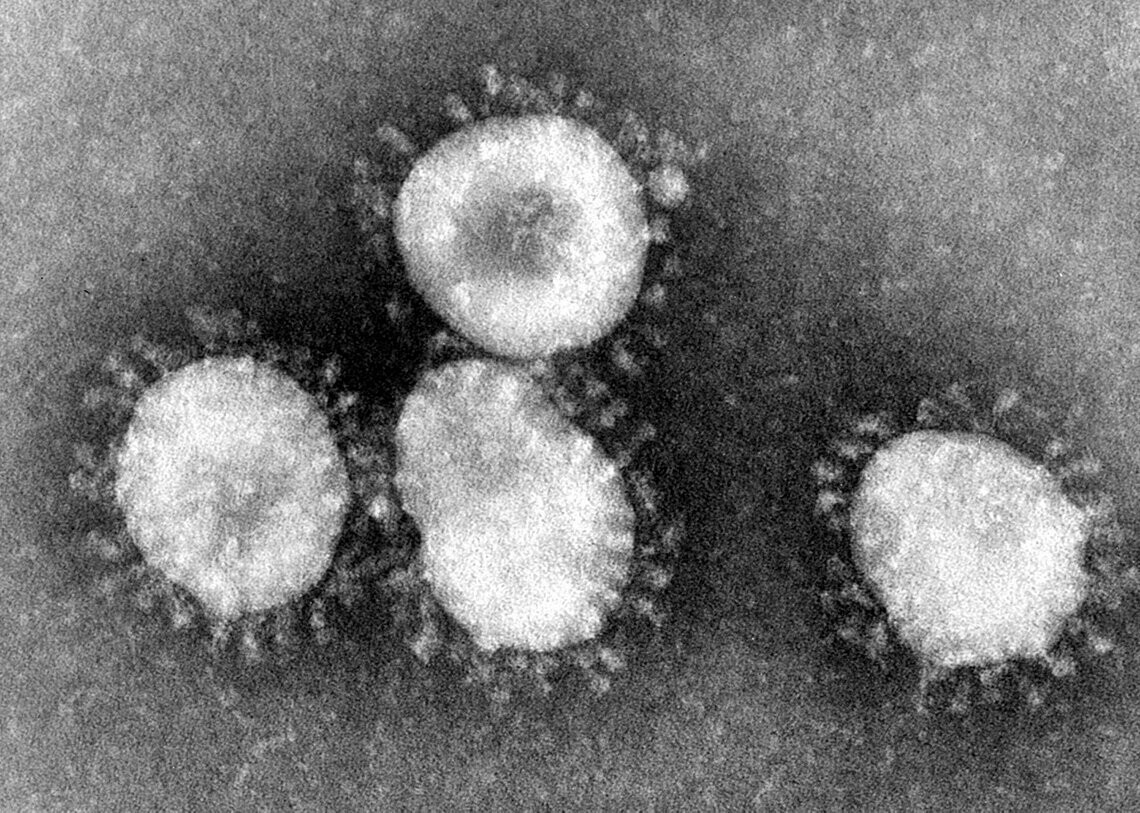

A virus is a short strand of genetic material (DNA or RNA) enclosed in a coat of proteins called capsid, the form of which varies from one type of virus to another. The measles virus capsid has a spherical shape, that of influenza(adenovirus) is a twenty-sided solid (icosahedron), that of polio and the coronavirus looks like hairy spheres, and viruses that infect bacteria (bacteriophages) are shaped like spaceships with little legs for landing. Different structures but all tiny: the largest virus has a diameter of 300 nanometers, so a row of 3,000 of these ‘giants’ would be 1 millimetre long. The smallest one measures just 20 nanometres, to make a millimetre you would have to put 50,000 of them one after the other.

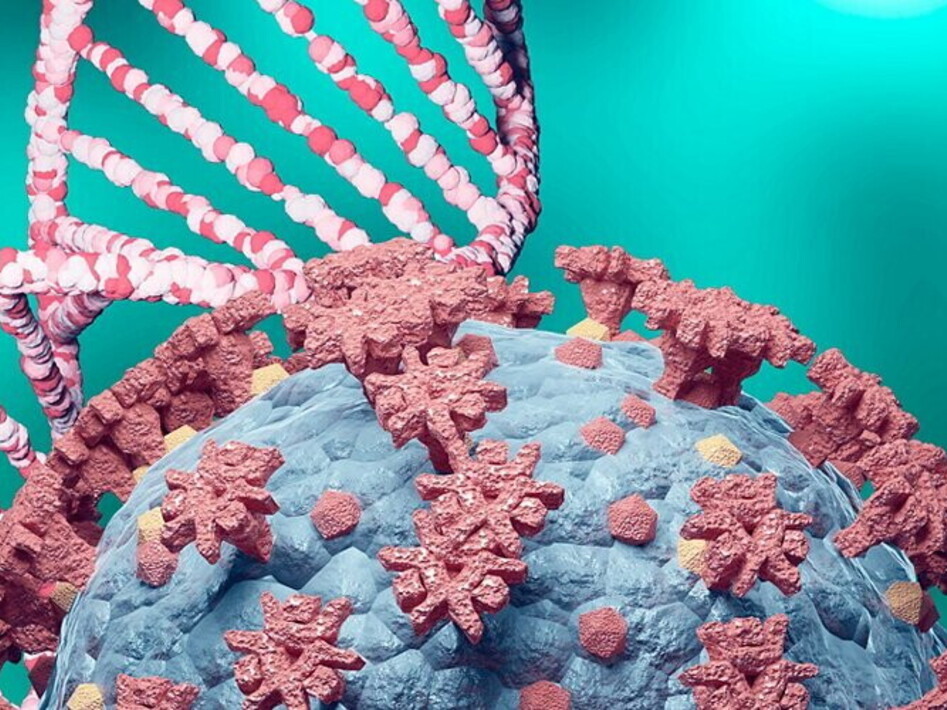

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that attack the respiratory system. They are spherical with the surface covered with spikes with crown-shaped tips, hence their name. Some are not very dangerous and can cause a simple cold, others cause more severe illnesses. Coronaviruses affect many animal species, those that infect humans are, for the moment, seven.

How viruses reproduce

Since viruses cannot replicate on their own, they must use the reproduction mechanisms of living cells, i.e. those of bacteria, fungi, plants and animals. Viral infection is an invasion: viruses enter cells and take them over.

The first step of an infection is recognition between the virus and the cell that will host it: a virus must “know” if the cell is suitable for infection. Viruses that attack plants, for example, do not make animals sick and vice versa. Right now, each one of us is breathing in viruses that are deadly to flowerbeds, but we can rest assured, what kills basil does no harm to us. The recognition between virus and cell is not sensory but chemical; viruses have no sense organs, in fact, they have no organs at all. The virus senses whether the cell is the right one, whether the spike proteins protruding from its capsid fit into those on the surface of the cell, like a key in a lock. If recognition occurs, the virus is absorbed by the cell: the cell digests it, destroys the capsid and releases the viral genetic content inside the cytoplasm.

At this point, the virus genes infiltrate the reproductive systems of the cell and instruct them to make new viral DNA (or RNA). These components assemble automatically and generate new viruses. The next step for all newborn viruses is to leave the cell all together and infect other cells, preferably those belonging to other organisms.

A virus is programmed to reproduce in abundance and spread everywhere and by any means. For example, some tickle our noses making us sneeze so that the mucus full of new viruses is sprayed into the air, ready to be breathed in by someone else. This is done by influenza, Ebola, cold, smallpox, meningitis, polio and the notorious COVID-19 virus, the latest coronavirus.

Coronavirus. Crediti: Wikipedia

Other viruses pass from one organism to another when organic fluids, such as blood, saliva or sperm are exchanged: this is how AIDS, herpes and hepatitis C viruses spread. There are viruses that are carried by insects, such as the yellow fever virus that uses mosquitoes. Other viruses spread through food: this is the case of those that cause hepatitis A and E.

Vaccines are the lethal weapons that defend us against viruses

Viruses are responsible for many serious diseases that afflict people, animals and plants. The first step in defending yourself against viruses is hygiene: washing your hands, for example, is a first and important defence. The other weapon is vaccination.

To understand how vaccines work, we need to return to the mechanism of recognition between viruses and cells. Our body’s immune system is the police headquarters that defends us at all times from attack by viruses and other pathogens. Lymphocytes are the police force produced by our immune system. They are special cells that patrol the whole body through blood and lymph and if they find viruses they respond by producing antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that attach themselves to the virus to make it harmless. They are like handcuffs that stop the criminal before he does any wrong. Lymphocytes are smart, but sometimes viruses are faster and can make us ill. A vaccine contains only little bits of a virus capsid, like the mug shots of delinquents. These little bits are not dangerous, but they show the lymphocytes the faces of the criminals. Thanks to vaccines, the lymphocytes already know what the viruses look like, so they can equip themselves with the appropriate antibodies before they show up. If viruses of the same type, but natural and active, later attack a vaccinated organism, the immune system is already prepared to deal with them.

Cows and the brilliant doctor

The term vaccine clearly derives from vacca (the Latin word for cow). But why does a medicine have a name deriving from the Latin word for cow? Smallpox is a terrible viral disease that has killed millions of people around the world. Edward Jenner was an English country doctor who around 1770 observed that milkers and cattle rearers did not get smallpox. In those years the disease was killing off people all over Europe: 20.000 dead in Paris, 60,000 in Naples, 40,000 in England.

The smallpox virus that attacks cattle can be transmitted to people but is not lethal; Jenner knew this well, so he sensed that contact with sick animals could make humans immune. He therefore tried injecting the infected serum of a bovine pustule into the body of a young patient: the boy did not catch smallpox. After more than 20 years of study, the country doctor perfected the invention that has saved, and continues to save, billions of lives. The vaccine still bears this name today in memory of Jenner’s studies. Thanks to vaccines, smallpox no longer exists. The last case of poliomyelitis in Italy dates back to 1982. It is worth remembering this when we have doubts about the effectiveness of vaccines.

Not all viruses are dangerous or harmful: some have proved to be valuable allies for several important human activities. In recent years, researchers have been studying the use of certain viruses in the biological control of plant pests. The mechanism is simple: treating animals or fungi that are harmful to crops, for example insects that eat leaves, with viruses capable of making them ill. Biotechnology is another field in which viruses are used. Viruses are used to induce bacteria to produce useful molecules. Insulin, growth hormone and erythropoietin, which stimulates the production of red blood cells, are now produced in this way.

An interesting fact: The use of the word influenza to indicate seasonal viral ailment goes back a very long way. Once it was thought that diseases were caused by the influence of the stars on people’s health. Even as late as in 1910, there were those who speculated on the terror generated by the passage of Halley’s comet and put canisters of purified air on the market as a cure for the deadly miasms released by the comet. An advertisement for the Michelin Bottle was published by the Corriere della Sera: it featured a cartoon showed a smiling family holding a bottle to their noses while driving in a car down a street full of people and animals dying because they did not have the miraculous pure air.

By Andrea Bellati