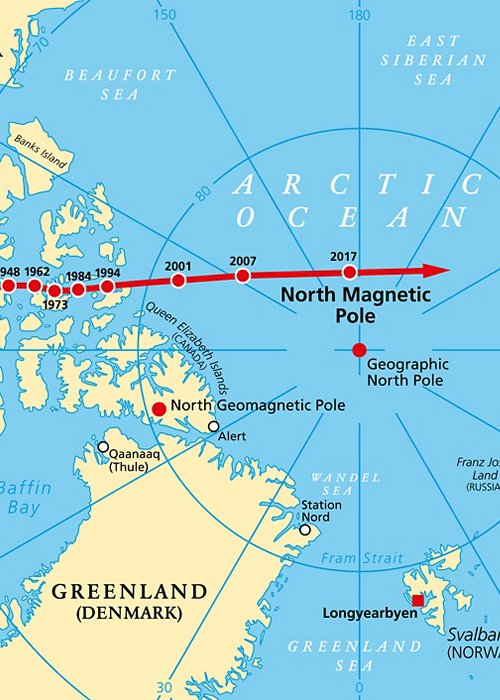

In recent decades, the magnetic North Pole has exhibited unexpected movement, not only shifting but also heading eastward from its historical location above Canada. This phenomenon has piqued the curiosity of scientists and climatologists, as it could have implications not only for navigation but also for the global climate. But why is the North Pole moving, and what are the consequences? The geographic North Pole is a fixed point where the Earth’s axis of rotation meets its surface. In contrast, the magnetic North Pole, where the Earth’s magnetic field lines converge vertically and compasses point, is not as stable. The magnetic pole has been on the move for decades, with its pace quickening in recent years as it shifts from west to east toward Siberia. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its updated World Magnetic Model a year early. It is usually updated every five years to ensure accuracy and safety for maritime and air navigation systems, but also to provide useful information in military and civil fields such as rescue operations, and even for smartphone compasses. The early publication of the new model “became necessary when it was observed that the magnetic field measurements made by satellites and geomagnetic earth observatories no longer matched the data from the old model produced in 2015”.

Over the years, this movement has shown a general eastward direction, albeit with variations in pace and speed. In the 19th century, the magnetic North Pole was closer to Canada but eventually began shifting toward Siberia, Russia. Today, the magnetic North continues to move, with its speed significantly increasing in recent decades to approximately 55-60 kilometres per year. Since the 1830s, the Earth’s magnetic North has shifted 2,250 kilometres eastward. Between 1990 and 2005, the pole’s movement speed rose from less than 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) per year to about 50-60 kilometres (31-37 miles) per year, according to a 2020 study. If this trend continues, scientists estimate the magnetic pole will shift another 660 kilometres eastward, and by 2040, compasses will point more eastward than true north. The South Pole is also in motion, and, like every 300,000 years, the magnetic poles of North and South are expected to reverse.

By Filippo Spanedda, 3A – Liceo Scientifico Vittorio Veneto, Milan