“You do not really know your friends from your enemies until the ice breaks.”

Inuit proverb

Passed down from generation to generation, this saying probably didn’t foresee that, one day, it would be the Arctic ice itself that would begin to break—yes, the ice of that region of the Earth that surrounds the North Pole. Unlike Antarctica, the Arctic is not a continent, has no fixed boundaries, and is made up of the northernmost extensions of the Eurasian and American continents, along with the Arctic Ocean which, when frozen, forms sea ice (the well-known floating ice of marine origin). By convention, the Arctic is considered to include everything north of the Arctic Circle, that is, “above” latitude 66°33’39’’.

The Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route

Over the past two decades, the unfortunate climate “records” that have led to the melting of polar ice have triggered a genuine race for the Arctic, attracting the attention of numerous governments and opening the way to increased maritime traffic. The Arctic region is rich in raw materials and energy resources, and if it were to become completely ice-free year-round, it could open up several sea routes that are significantly shorter and more advantageous than Atlantic or Mediterranean routes—especially in light of the current crisis in the Red Sea and the possible decline of the Suez Canal, as well as the growing constraints of the Panama Canal. In recent times, increasing attention has been given to the famous Northwest Passage (NWP)—a sea route that, skirting the northern part of the American continent, connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean—and the “Northern Sea Route” or NSR (also known as the Northeast Passage), which connects Europe and Asia by passing through the Arctic Ocean. To these two routes we can add the Transpolar Sea Route (TSR), which links the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans by crossing the centre of the Arctic Ocean: this is the least navigable route due to the ice covering the North Pole.

One record that made headlines worldwide was set by The World, the first cruise ship to complete the Northwest Passage in 2012. The following year, the Nordic Orion earned the distinction of being the first large cargo ship to make the same journey for commercial purposes, transporting a load from the Canadian port of Vancouver to the Finnish port of Pori, saving about 1,850 km (and €60,000 in fuel) compared to the traditional route through the Panama Canal. In the summer of 2017, it was the turn of the Russian oil tanker Christophe de Margerie, the first ship to travel the Northeast Passage without the support of an icebreaker. The vessel, owned by the Russian government, departed from Norway and arrived in South Korea in just 19 days—taking about two-thirds of the time usually required to complete the “traditional” route via the Suez Canal.

According to data updated to 2024 and published by Rosatom, the state-owned operator responsible for transport along the Northern Sea Route, traffic last year reached 37.9 million tonnes, an increase of 1.6 million compared to 2023—the highest volume ever recorded. In addition, the number of transits increased, with 3 million tonnes of cargo in transit—another historic record—alongside a rise in the number of permits issued for passage through NSR waters. Arctic routes therefore represent a major challenge for Arctic countries in commercial, geopolitical and environmental terms. For Italy, on the other hand, they pose a potential threat, as its ports risk being excluded from the world’s main shipping routes.

At a time in history when technology and scientific progress make everything seem within reach, events like these risk going unnoticed, failing to capture our imagination. But if we stop for a moment to reflect, it’s easy to see how they profoundly mark the course of human and planetary history, redrawing the geography of trade and setting new balances and new powers on the geopolitical chessboard.

Arctic: climate change and new economic interests

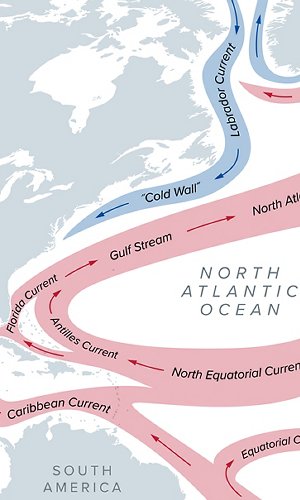

The Arctic is one of the Earth’s regions most sensitive to climate change, for many reasons, including the fact that global warming has a very significant impact on sea ice, land glaciers and permafrost (frozen ground). The melting of these various types of ice affects the entire ecosystem, both locally and globally, impacting the Arctic’s and the planet’s physical, chemical and biological processes (just think, for example, of the effects on ocean currents!). The transformations currently underway are highly complex, strongly influence one another, and the construction of models capable of accurately predicting what will happen in the future—both regionally and globally—is a very ambitious task even for scientists.

But one thing is certain: climate change is radically altering the way governments, industries and traders all over the world view a portion of the globe that is becoming increasingly important and more appealing to the economies of several countries. We already talked about the new sea lanes that the thinning (Arctic ice thickness has decreased by about 40% in just half a century) and melting of the ice are opening up, and about the growing interest in northern maritime routes, which in some cases allow for savings in both time and money compared to traditional routes. But that’s not all. Just think of the energy resources—hidden and unexplored for millions of years beneath the ice (sometimes several kilometres thick)—which are now accessible at lower cost due to global warming and new extraction technologies. And we’re not talking crumbs: according to estimates released by the CNR (Italy’s National Research Council), the Arctic’s oil resources account for around 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil, and when it comes to gas, that figure rises to even 30%.

Governance and geopolitics

These economic interests arise in the context of Arctic governance, which is far from simple. The differences between the Arctic and Antarctica are not only geographical, geological and biological. Unlike Antarctica, in fact, the Arctic is not governed by a dedicated international treaty, although in 1996 the Arctic Council was founded—an intergovernmental forum, of which Italy is an Observer State, focused on governing the Arctic and its Indigenous communities. The countries that make up the Arctic are eight: Canada, Denmark (Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia and the USA, and under international law, UNCLOS (the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea) states that each nation may define the extension of its continental shelf up to 200 nautical miles (approximately 370 km), where it may exercise exclusive rights over the exploitation of natural resources (Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ). A request to extend this limit may be submitted—up to 350 nautical miles—to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

Despite international law, however, disputes are frequent, and the wishes of Indigenous populations are often largely disregarded. It may seem incredible to us that anyone could live in such a hostile climate, but thousands of people live in the Arctic, belonging mainly to eight different Indigenous groups: the well-known Inuit, but also the Yupik, Aleuts, Yakuts, Komi, Nenets, Tungusic peoples and Sámi. It’s not just the countries bordering the Arctic that are vying for a stake in the region: China and India, for instance, are investing heavily in the area and seeking to consolidate their presence through partnerships with Russia.

There is no doubt that climate change is having major direct and indirect effects, not only on the lives of local communities, but also on the global geopolitical landscape.

According to some, we are witnessing a new Cold War. In every sense of the word...