Is there life on Venus?

16 September 2020

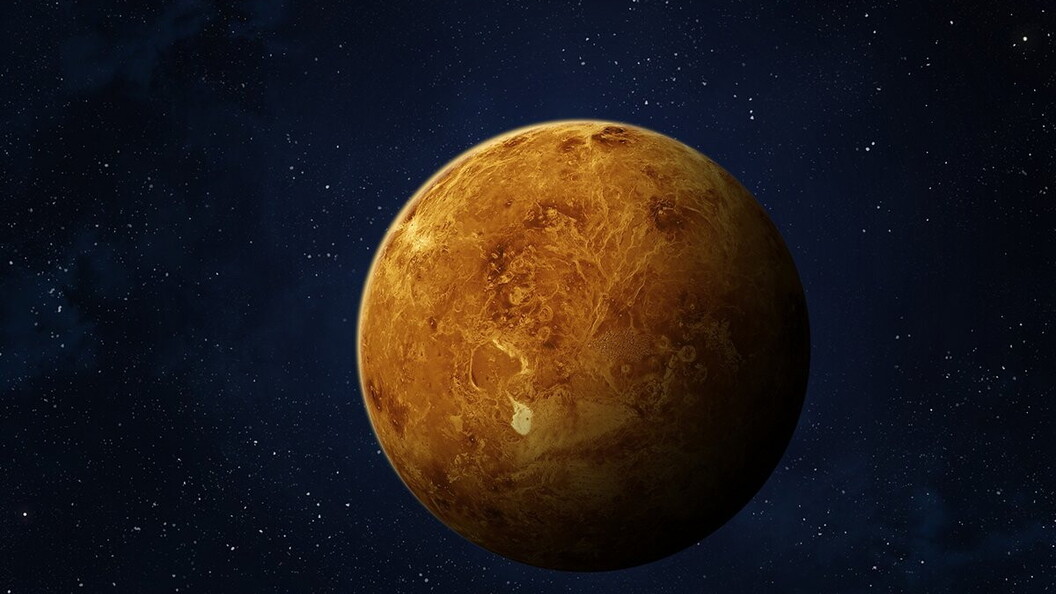

Planet Venus

At the opposite end of the habitable belt there is Venus, similar in size and “geological” characteristics to our planet – that is, like Earth, it is a rocky planet. However, unlike Earth, Venus is probably one of the most inhospitable places in the Solar System: the temperature on the ground is about 500°C, higher than that recorded on Mercury, the planet closest to the Sun, so the Sun is not directly responsible for that infernal climate. The blame lies with the very extreme greenhouse effect on Venus. We know that the greenhouse effect is due to the presence of gases that trap solar radiation and heat the atmosphere. The main greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, water vapour and nitrogen oxides. On Earth we are rightly concerned because the amount of carbon dioxide is increasing due to human activities and with the increase in CO2, temperatures are rising. The Earth’s atmosphere contains 0.04% carbon dioxide. CO2 accounts for 96.5% of the Venusian atmosphere; that’s why it’s so hot on Venus and there’s not even a drop of water. In addition, the sky of Venus is crossed by clouds of sulphur dioxide, a gas that is highly toxic on Earth; thousands of volcanoes the size of Etna continuously erupt lava and poisonous gases. The atmosphere of Venus is so dense and heavy that the pressure on the ground is 90 times greater than on Earth. If there’s one place that looks like hell, it’s Venus.

And yet…

The news is very recent: in the upper cloud decks of the Venusian atmosphere, around 60,000 meters above sea level, where it is a little “cooler”, there is a strange molecule called phosphine. Phosphine is shaped like a pyramid, with one atom of phosphorus and three of hydrogen at the top. Phosphine can be found on Earth too: some of it is of industrial origin – the molecule, in fact, is also a pesticide used in agriculture – the rest is of biological origin. Anaerobic bacteria, which grow in the absence of oxygen, absorb phosphorus from the environment in the form of phosphate and combine it with hydrogen to obtain energy; these bacteria release phosphine as a waste product. Therefore, since there are certainly no industrial plants producing pesticides on Venus, atmospheric phosphine could be of biological origin: in short, there is life on Venus! That is, something similar to the bacteria that withstand extreme conditions on Earth (in volcanic fumaroles at the bottom of the oceans or in the scalding pools of geysers) could live on Venus and release phosphine into the atmosphere.

The news is sensational, but the team of astrophysicists who made the discovery is holding back: the group of researchers led by Jane Greaves, astrophysicist at Cardiff University in Wales, says that the biological origin of phosphine is yet to be demonstrated. It is true that the small molecule is one of the traces that life leaves in the environment, but it is also true that we still know little about the geophysics of our “sister planet” and it may be that phosphine develops from unknown chemical reactions. For example, the electrical discharges of lightning, in that atmosphere so dense and full of volcanic gas and dust, could produce that bit of phosphine detected by the instruments that carefully scrutinize the planet. All we have to do is send a new probe to analyse the Venusian atmosphere directly. Venus is “easier” to reach than Mars. Since 1961, 28 probes have reached the planet to collect valuable information. Most of them stayed safely in orbit. Others landed and succeeded in sending data before the heat and pressure destroyed them. We have photos of the surface of Venus that confirm the planet’s completely deserted appearance. The next probe will be sent in 2026: it’s Russian and is called Venera-D. Its task will be to “sniff” the atmosphere and confirm, or deny, the presence of phosphine.

By clicking here you can consult the article in Nature Astronomy describing the incredible discovery (in English).

By Andrea Bellati